Churches in a post-Christendom culture need porches. Some will be larger and more formal and others small and informal. The more practical-minded of my readers, however, probably want more details about how these porches can be built and would like more examples of them. So I will write one more article in the quarterly that gives some of that information.

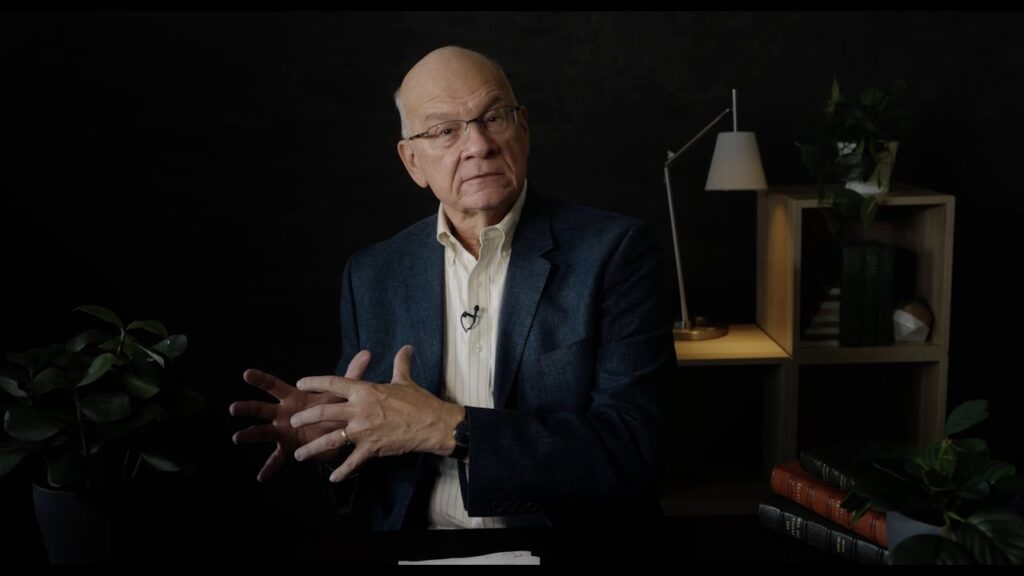

That was the way Tim ended the first part of Lemonade on the Porch, printed in the Spring Gospel in Life Quarterly.

I mentioned to him that he owed me the second part several times while he was receiving treatment in April at the NIH, mostly to give him something to think about, and he did…think about it. Unfortunately, he did not write it down (although he told me in the Emergency Room that he had written the entire article in his head), but he became too weak to either write or dictate it.

So I asked James Eglinton, Meldrum Lecturer in Reformed Theology at the University of Edinburgh and one of Tim’s conversation partners on this subject, if he would write the second article. He graciously agreed.

At the end of his article is a link to suggestions from Redeemer pastors on things they are already doing or hope could be done to build new “porches” to engage with those who don’t yet believe.

– Kathy Keller

In the previous Life in the Gospel Quarterly, Tim Keller published the first of an intended two-part series of articles under the title, ‘Lemonade on the Porch: The Gospel in a Post-Christendom Society.’ The background to that was a lecture I had given on the Dutch theologian Abraham Kuyper’s observation that when a culture is deeply affected by Christianity, it prepares its inhabitants for direct encounters with the faith when they go to church. In Christendom-era Europe, this was the case for many centuries: to be formed by European culture was to imbibe rhythms of life and assumptions that were profoundly Christianised. In Tim’s way of putting it, that culture gave people dots (why do I exist? How should I relate to other people? How do I live with myself in view of my own human failings? What do I do with my sense of the transcendent? How do I deal with mortality?) that the church then connected. Going to church enabled you to make more sense of the life that your culture had already taught you to intuit.

To describe this, Kuyper borrowed the image of the Old Testament temple’s holy place and forecourt, which he applied, respectively, to the church and its surrounding culture. To enter the forecourt was not the same as entering the holy place, but it was nonetheless a space that prepared you for all that happened in the holy place. A century ago in the Netherlands, Kuyper observed that the church’s historic forecourt, cultural Christendom, had all but disappeared. Mainstream Dutch culture no longer prepared people to encounter the church and hear a message that made more sense of their prior intuitions. Instead, the church’s message was discordant.

Kuyper left a distinct challenge to the church in his own day, and in ours: in a post-Christendom culture, how do we help churches think through and develop new forecourts that help secularized Westerners who have neither direct and personal familiarity with the church, nor indirect and (in some sense) harmonious attunement to Christianity through prior cultural formation?

Tim’s own choice of image was the porch: a place you can enter without going into someone’s home, but that helps you see what to expect beyond the front door, and a place through which the house affects the street. What kind of porches might the church build in a post-Christendom culture?

Tim discussed those questions at length with me, and with Michael Keller, although his own part 2 went unwritten as his health declined. However, Michael and I continued the conversation, the result of which is a part 2 of sorts: a paradigm for porch building that focuses on hospitality, cultural apologetics, and forgiveness.

A Paradigm for a Culture of Confusion

What kind of cultural formation do people receive in the post-Christendom West today? Through philosophers like Charles Taylor, Philip Rieff, and Chris Watkin, we see that our own day is marked by a strange synthesis of Christian and non-Christian ideas and intuitions, rather than the replacement of Christianity with its polar opposite. Across the West, older Christian ideas and intuitions lie buried under the surface of secular culture like magma smoldering beneath tectonic plates. Often, that magma rises and creates fissures and ruptures on the surface. Sometimes, it erupts. In that sense, the waters of Christendom haven’t been replaced wholesale by, say, purely atheistic waters. Instead, everything is much more diluted. Western people today grow up being taught by Christ (‘turn the other cheek,’ ‘forgive,’ ‘love your enemies,’ ‘deny yourself’) and Nietzsche (‘what doesn’t kill you makes you stronger,’ ‘you have to be selfish’) at the same time. In contradictory ways, both outlooks sink deeply into the kind of mentality that people learn by swimming in those mixed waters.

The gospel makes a confusing first impression on secular Westerners because some aspects of today’s mainstream Western mentality are the products of Christianity (for example, the assumption that sex should be based on consent rather than coercion), whereas other closely related strands (for example, the celebrated use of consent for casual, transactional sex) are based on the rejection of Christianity. At first introduction, it can be hard for Westerners to tell whether the gospel is good or bad for them, or whether they love or hate it. What kind of paradigm might help such people make sense of Christianity?

When I asked Tim to speak about the importance of porches in American culture, he said, “there are those who see that the forecourt provided by the culture has gone away and now the culture mainly creates hostility to Christianity” (the ‘negative world’ thesis, a message Tim had been preaching for some time before the term gained traction). Tim affirmed that view’s realization that the forecourt had changed for the worse. He also thought that this insight had yet to dawn on most American churches, who tended towards older patterns of liberal accommodation of secular culture, total withdrawal from it, or outright war against it. Alongside these, he described churches that had underestimated just how great a sea change had happened in Western culture, and that continued to rely on an “old fashioned Christendom model—just preach to the choir and hope there are enough choir members still out there in the community to come to church and get converted,” alongside the ‘seeker sensitive’ movement, which “does not abandon orthodoxy but plays it down and tries to show ‘relevance’ and hope people will come and be converted.”

“What these five approaches all have in common,” he wrote, “is that they have no interest in (or maybe no conception of) the church creating a forecourt for non-believers.”

Tim thought that the lack of well-developed forecourts (or porches), or even the awareness of their importance, presents an obstacle for the church in Western culture. How should churches help those whose first impression of it is such a jarring, disjointed one? Tim ended ‘Lemonade on the Porch’ with a promise to detail how such porches might emerge, and what they might look like: ‘Some will be larger and more formal and others small and informal.’

In our conversations, he sketched out a paradigm for these porches focused on hospitality and forgiveness. This way of imagining the content and implications of the gospel as themselves shaping the character of distinct porches is important. For the forecourt to serve its purpose, it must be animated by (and introduce people to) the same realities of the gospel.

Hospitality

In 2008, Tim preached on the biblical picture of hospitality (philoxenias, ‘love of strangers,’ as a direct opposite to xenophobia, ‘fear of strangers’). Christians are both recipients and conduits of God’s hospitality to others. The hospitality that we receive from Christ, “the ultimate host” who entered “the ultimate homelessness” for us on the cross, serves as an impetus for all hospitality—from large-scale endeavors like supporting organizations that serve the poor and marginalized to inviting a neighbor to coffee in your home.

The hospitality that we receive from Christ, “the ultimate host” who entered “the ultimate homelessness” for us on the cross, serves as an impetus for all hospitality…

However, even such simple, unguarded, gratuitous actions are difficult—or even counter-intuitive—for many secular Westerners today. In the first place, modern secular identities are fragile and competitive, and for this reason they struggle with hospitality. For the reasoning behind this, listen to this talk on ‘Modern Identities,’ given by Tim in 2017. There, he argued that modern Western people had shifted from traditional identities grounded in things outside of themselves (in our families or communities) to a basis within themselves (in the outward expression of inner desires). In that shift, modern identities adopted a new core assumption about other people: ‘you exist for me, and not me for you.’ That default isn’t fertile ground for hospitality.

Secondly, Tim argued that in the modern West, “you find out who you are by demonizing somebody.” In modern secular culture, for us to be us, we need our opposites to be our opponents. Xenophobia comes more naturally than philoxenias. We’re geared towards hostility more than to hospitality. This is part of why, for example, secular Western identity often struggles to let its guard down even in the company of like-minded people: increasingly, we think and talk of allies rather than friends.

In part one, Tim wrote of how some porches would be small and informal. Imagine, as a pop-up forecourt, a public talk organized by Christians, where Christians and non-Christians are welcome to ask questions and to express critique and disagreement in an atmosphere marked by an amiability and honesty (which is to say, intellectual and social hospitality) rarely seen in today’s febrile secular spaces. How might that kind of porch help a non-Christian make more sense of church, or perhaps even be more interested in attending? It might provide a momentary glimpse of how the gospel offers a less brittle, less performative, more unguarded identity and way of relating to others. The curious non-Christian who steps into a forecourt marked by that kind of social and intellectual hospitality might just find, upon attending church, that God is supremely hospitable—even to his most avowed enemies. Perhaps then church might make more sense than it would have without that pop-up forecourt?

Drawn by hospitable forecourts, curious non-Christians who then move into the church must find places of joyful hospitality. “The opposite of joy,” Tim once preached, “is not sadness. It’s hopelessness. It’s having nothing to rest in. Happiness rests in blessings, but joy rests in the blesser. You can be joyful even when you’re sad. We should be experts in joy.” That joy abounds. Indeed, because the gospel teaches us to ground our identities in a reality beyond our selves, it also gives us deep resources with which to derive joy from other people.

It is not the case, of course, that secular Westerners never celebrate the joys and successes of others. Common grace still abounds on that front. However, the reasons for that celebration are not derived from the kind of competitive, performative modern identities described in Tim’s talk. Left to run on that basis alone, the successes and joys of others, even of those in our own camp, are more or less irrelevant to our own identities. To the modern Western identity, the world is more like an empty stage (as a place to perform) than a classroom (a place to be formed, as was the case for traditional identities). It teaches us to imagine other people primarily in their usefulness to us in the outward expression of our own inner desires: if your current partner doesn’t help you express those desires, you find a new partner, and so on. It imagines other people as instruments to joy, but where that joy can only be found within ourselves. On the sole basis of that kind of identity, there is no compelling reason to derive joy from the lives of others (and certainly not from your cultural opposites/opponents). Because of that, when secular Westerners celebrate the joys of other people, they unwittingly draw on borrowed Christian capital. However, when the church commits to being a culture of joyous hospitality for others in porches and houses alike, the church draws on its own inheritance and lives out its own good news.

In the secular West, in a culture that overstates the weak reasons for its celebrations, Christians must be careful not to understate the strong reasons for their hospitality and celebrations. Indeed, one risk is that churches give no (or only superficial) reasons for why they do so. On that point, Tim saw that a forecourt needs to combine Christian practices with the clear expression of their underlying principles. Herein lies the challenge: if two groups—Christians and their secular neighbors—practice the same thing (in this case, hospitality), can either provide better reasons for why?

Apologetics

We can think of hospitality both as a distinct kind of porch, and also as the basic culture to be found in all porches. In both cases, hospitality is situational. It deals in regular, organic, sometimes unplanned practices of generosity between individuals and groups whose paths cross in one place or another. As a practice, though, hospitality needs to be accompanied by apologetics, which is normative in scope, and deals with probing claims about us, our world, and God.

However, when the church commits to being a culture of joyous hospitality for others in porches and houses alike, the church draws on its own inheritance and lives out its own good news.

Here, we are dealing specifically with cultural apologetics. Cultural apologetics in the modern West aims at two things. First, it addresses individual secular Westerners in order to explain how and why their distinct perspectives on the world are not neutral, unbiased, or simply the expression of some disembodied, culturally untouched, authentic inner self. Rather, it shows them that their individuality has taken shape somewhere instead of nowhere: in a particular family, in a school system, in a cultural moment, in a local community, in an individual’s distinct temperament, and so on. Cultural apologetics challenges people to become aware of, and then to question, the untested assumptions about life and the world that they inherit passively and then live by in that setting.

Second, it helps individuals see that they belong to, and are formed by, vast cultures that are themselves shaped by particular worldviews. For example: while a group of Americans will probably think about themselves primarily as individuals who differ from one another (“I’m not like her, she’s a Democrat from California and I’m a Republican from Tennessee,”) it is no less meaningful to say that when we set them alongside a group of people from mainland China, for all their in-group differences the Americans will nonetheless strongly resemble each other as a group, and will have all sorts of shared differences to the mainland Chinese group. To explain this, we need to start talking about grand-scale worldviews (in this case, Christian and Confucian) and their role in shaping cultures at large.

Most people have no frame of reference in thinking about what it would be like to come from somewhere very different, or to be someone else from the same kind of place. Cultural apologetics provides that frame of reference. By doing so in the context of the secular West, cultural apologetics deals with explaining the history, workings, and shortcomings of secular modernity to the people who depend on it most but think about it least: secular Westerners.

What is the value of doing so? In our conversation, Michael Keller provided an example. He had just preached a sermon on how “the new thing is to disempower the powerful.” Questioning a prominent Western cultural narrative, he argued that “the problem is, if you have enough power to actually do this, you should probably also disempower yourself… and you don’t usually do this.” When engaged in that kind of apologetic, the goal goes far beyond a mere ‘gotcha moment’ form of sophistry. Instead, it aims to show that when operating on its own terms, secular Western culture cannot deliver on its noble intention of justice (rather, to quote Chris Watkin, it can only ever produce ‘unjust justice’). In Dan Strange’s term, the apologetic aims to show that Christianity ‘subversively fulfills’ that striving for justice in Christ.

In that approach, the goal of cultural apologetics isn’t just to craft narratives of how secular modernity works. It goes beyond this to show that Christianity out-narrates every other account of life in the world. The porch opens directly into the church.

Last year, I asked Tim about whether by incorporating that kind of cultural apologetics in preaching, he could envision a way to include elements of the forecourt in the church itself. He answered, “Yes, one’s preaching can make a Sunday service, to a degree, a ‘forecourt’ for inquirers. That is exactly what I was trying to do in my preaching.”

That part of the life of the church, that section of the sermon, wasn’t totally unfamiliar to a non-Christian who had already been on the porch of cultural apologetics. Alongside this, Tim spoke of a literary forecourt that was clearly outside of the church. To him, the culture-upending effect of Tom Holland’s Dominion was an excellent example of this. (See Tim’s review here.) More such books need to be written.

Beyond the worship service—which can be a ‘forecourt’—there needs to be lots of other spaces where inquirers can have the Christian remnants of their beliefs (à la Tom Holland/Charles Taylor) strengthened and where we can make visible to them ‘the waters’ they’ve been swimming in so they can see alternatives, where they can doubt and question and feel accepted as they do so, where they can hear and see the offers of Christianity presented in ways that connect to their own baseline beliefs and longings, where they can actually taste some of the sweetness of Christian community, where they can see modeled mature Christian faith.

– Tim Keller

Helping secular Western people see that their untested assumptions about life and the world are a strange synthesis of Jesus and Nietzsche, or that Christianity props up (and uniquely fulfills) cultural goods that they themselves cherish, might not make their first acquaintance with the church altogether palatable, but it could make them more reflective about why some parts of the church’s message seem to ring true, whereas other parts are counter-intuitive.

Forgiveness

In comparison to hospitality (situational) and cultural apologetics (normative), forgiveness is existential. Indeed, the existential power of forgiveness holds together the porches of hospitality and cultural apologetics. If we have no capacity to forgive, hospitality is impossible. Forgiveness is hospitality’s constant assumption—and when hospitality has to give an apologetic for its own existence, sooner or later, it will have to talk about forgiveness. But forgiveness also has to provide its own apologetic: why forgive, rather than be indifferent to wrongs, or bear grudges, or mete out your own revenge?

In his atheistic philosophy of domination, Nietzsche recast an acceptable kind of forgiveness not as a trait of weakness, as he saw it in Christianity, but instead as an affirmation of strength. In his view, we can only relate to forgiveness as the one who asks for it, or the one who grants it. In a life that strives for domination, you should want to be the one who asks for forgiveness (as the person who injured someone else because you were more powerful than he was) rather than the person who has to grant forgiveness (as the person who was injured by someone stronger). As such, forgiveness is only a good thing when it confirms your domination over a weaker person. Asking for forgiveness then becomes a proxy for having dominated. By contrast, to Nietzsche, the act of granting forgiveness was a mark of weakness. He thought that on this point, (as so many other points!) Christianity was wrong.

The goal of cultural apologetics isn’t just to craft narratives of how secular modernity works. It goes beyond this to show that Christianity out-narrates every other account of life in the world.

However, this way of approaching forgiveness remains out of step with most secular Westerners today. Imagine, for example, you had to choose between inflicting harm on someone else (which would mean asking for forgiveness), or being the one upon whom that harm is inflicted (which would mean granting forgiveness). Which would you choose? While many secular Westerners would still rather receive harm than inflict it (based on an intuition of kindness rooted in Christianity), Nietzsche’s logic pushes you in the opposite direction. While there are better and worse ways to be strong rather than weak, the only real choice remains: to dominate or be dominated, to be the one who asks for forgiveness or the one who grants it.

Nietzsche believed that human nature was inherently selfish, and saw Christianity as being fundamentally anti-nature in requiring its followers to deny self, and by extension, grant forgiveness. In Tim’s last book, Forgive, he addressed the same issue: ‘the difficulty of forgiveness lies in that it is unnatural—it is not the nature of things. It is counterintuitive to our basic human instincts and nature.’ His way of getting to that, of course, was very different to Nietzsche: as the image of a holy God, humanity’s original state, righteousness, had no inherent need to ask or receive forgiveness for sin. Because we were made to be perfect, in one sense, we shouldn’t need forgiveness. But because we are fallen, we have no more urgent existential need. Forgiveness might be unnatural, but it is essential to every human life.

“There’s Much to Do!”

The goal of the forecourt is to offer something that secular Westerners need as human beings (made in the image of God), and to an extent still partially intuit (in the confused heritage of post-Christendom), but that they cannot get to on their own. A liveable approach to forgiveness is one such thing. What will it look like to build forecourts of forgiveness that lead into the church, and that include both horizontal (human-to-human) and vertical (God-to-humans) dimensions? Tim himself wasn’t sure, although the power of forgiveness stood out to him. His closing words to me on this were simply, “There’s much to do!” Like him, I am also unsure of what this will look like. And in that regard, this follow up is probably less practical than Tim had in mind. It is an attempt to flesh out the why and the how of a paradigm. For now, though, the task of building those porches—as diverse as they will be—is over to the church.

Editor’s Note: Remember that the definition of a “porch” is a half-way meeting place where those who don’t yet believe can mingle with believers, get to know them, observe their behavior, listen to various presentations of Christianity, and generally look into the life of faith before being called to make a profession of faith. Here are some ideas and things already being done by sister Redeemer churches in NYC. Leaders from other churches are invited to send in examples of things that have worked in their setting to create safe spaces for believers to bring their unbelieving friends by emailing us at support@gospelinlife.com.