Christians and Culture

Roman culture was saturated with idol-culture. Every town and people group had their own particular gods, as did every guild and craft, and even most homes had household gods. There were “gods many and lords many” (1 Corinthians 8:5) that oversaw every aspect of the society. If you visited any country, city, or home, you were expected to participate in some ritual of honor to the house gods, which usually involved eating food. Whether it was a gathering of craftsmen, a class in a school, a town council, or an audience for an artistic presentation—it was done in the name of a god. So every morning there were animals sacrificed, prepared, and eaten in tribute to the deities in opening exercises across the city.

This meant that when people became Christians they were faced with an enormous challenge. They were forbidden to honor idols in any way. But schooling, socializing, political discourse, employment, and commerce were normally done in settings that paid tribute to idols. Not only that, but in an age before refrigeration, a great deal of the food and especially the meat sold in the marketplace and the shops of the city had been dedicated to pagan gods in various ceremonies earlier in the day.

Did this mean Christians had to withdraw almost completely from society? Some Christians believed they did. Since idolatry was behind nearly every gathering and even the food in the shops, they wanted to withdraw deeply into the church and to form their own alternate social world. Others, however, thought that there was no real problem with participating in society (with the obligatory idol-feasts) as long as you didn’t worship them in your hearts.

The result was a bitter divide between Christians in Corinth. Believers with the same doctrinal beliefs were grievously split over how to relate to the culture around them. Those more on the side of withdrawal (the ‘conservative’ party) accused the other side of compromising with the spirit of the age and giving in to idolatry. They pointed to the importance of being holy. The other side (the more ‘liberal’ party) thought of their opponents as hopeless legalistic. They pointed to their Christian freedom, and insisted: “I’m not going to let you compromise my freedom in Christ!” Each side – the cultural withdrawal party and the cultural engagement party – saw the other as being unfaithful to the Lord. [] [1] For this background see Roy E. Ciampa and Brian S. Rosner, The First Letter to the Corinthians, Eerdmans, 2010, 367-371.

Today, many Christian believers—who often share virtually identical doctrinal beliefs—are just as divided over how to relate to our increasingly pagan culture even though the issues are often presented as political. Just to take one example, there are numerous Christians who adhere to the biblical teaching about the sanctity of human life and who are pro-life in their beliefs and sentiments, yet who are active in the Democratic party, which has a highly pro-abortion platform. Other believers insist loudly that such involvement is absolutely impossible for a Christian, that they must have nothing to do with the party, much less ever vote for a Democrat.

Then there is the issue of ‘systemic racism.’ Some Christians are concerned to listen to voices in the culture speaking of this and then to go to the Bible in order to possibly rethink their practices and beliefs. But others believe Christians should reject all the claims about injustice that come from the increasingly secular, progressive, and coercive wing of our postmodern society.

Therefore we should read 1 Corinthians 8-10 carefully. In these chapters, Paul addresses the ‘culture war’ going on within the Corinthian church. We must not get distracted by what appears to be a now-obsolete problem—meat offered to idols. These chapters contain theological and pastoral principles that are highly relevant for us today.

Paul begins by breaking down various aspects of idol-culture so we can see and address them individually. There were the ceremonies in which the priest sacrificed an animal for the god (10:14, 20). Then there was the consuming of the food as part of doing honor to that god (10:20-22). Finally there was the meat from the ceremonies and meals that had not been consumed which was sold in the marketplace (10:25, 28). Paul lays down three principles for navigating the issue. I’ll call them the worship, the freedom, and the love principles.

The Worship Principle

“For us there is but one God…through whom all things came and through whom we live” (8:8). Therefore, he says in 10:14-18 “Flee from idolatry” and proceeds to tell Christians they must not “participate in the altar” of an idol. Christians cannot be present when a sacrifice is made to a god. They cannot participate in any ceremony that publicly proclaims there are many powers and deities, thereby proclaiming the Lord is only one among many. That is a lie, and Christians can have no part in any observance that promotes that message to the world. On that basis, “Paul flatly opposed believers accepting any invitation to join in the open worship of the various pagan deities—for example, by taking part in meals held as part of a sacrificial rite in honor of a deity. To take part…would be ‘idolatry.’” [] [2] Larry Hurtado, Destroyer of the gods: Early Christian Distinctiveness in the Roman World, Baylor, 2016, 151. This was a rebuke to the overly ‘liberal’ party, the one that insisted that Christians need not absent themselves from any social gathering as long as their hearts were right.

Ciampa and Rosner make a helpful distinction between “objective” and “subjective” idolatry. Subjective idolatry [] [3] Ciampa and Rosner, 369. means to have one’s heart drawn to an idol-god, to love it and put one’s hopes in it. Objective idolatry was—regardless of one’s heart or one’s beliefs—to participate in a public ceremony that bore witness to the reality of an idol-god and strengthened that belief in the minds of onlookers. It was the latter that was the danger for the “cultural freedom and engagement” party. Even if you didn’t believe the god existed, to be present in such rituals was to promote the name of the god and therefore to commit idolatry.

Today, Christians who are engaged in the culture must consider whether, in doing so, they are actually promoting the gods of our society—sex, money, power, self-determination—to the world. If they are rising up in the secular business world, do they appear to be making money for the same reasons, adopting the same values, and by the same methods as everyone else? If they keep their Christian identities a secret or if they do not differ in their practices at all, the end effect could be simply to strengthen the appeal of the idols of wealth and power to the world. And are they making money by funding commercial projects that only serve to make our society more consumerist, more image-conscious, more absorbed in themselves? The same can be said in reference to Christians in the arts, or in the media, or in many other sectors of culture.

The Freedom Principle

Secondly, however, Paul wrote that “an idol is nothing at all in the world and…there is no God but one.” (8:8) “Idols” have no power to bless or curse us, because they are imaginary representations of imaginary beings. [] [4] It is true that in 1 Corinthians 10 Paul says that sacrifices to the gods are sacrifices to demons (verses 20-21). “…although the idols themselves do not have any valid spiritual reality and do not represent actual gods, there is a spiritual reality behind them in that they have been created at the instigation of demons…” Ciampa and Rosner, The First Letter to the Corinthians, Eerdmans, 2010, 479. The point is that idol-worship always enslaves the heart to created things and sin which the demonic forces use against us, much as the New Testament depicts Satan using and amplifying the sins of resentment or pride (2 Cor 2:11; Eph 4:27; 1 Timothy 3:7; 2 Timothy 2:26). Since there are no “gods,” the food itself has no supernatural power to separate you from God or pollute you morally or spiritually. “We are no worse if we do not eat and no better if we do.” (8:8) Then in chapter 10 Paul goes on to speak of a Christian’s conscience. He says that Christians were free to buy and eat any meat available at the market “without raising any question of conscience” about its origin (10:23-26). There is no Scriptural law binding the conscience against partaking. They are not committing objective idolatry or subjective idolatry to do so. A Christian should, he argues, have freedom of conscience to eat it.

Paul then addresses the issue of private dinners, which “were extremely common and served as a key to establishing the social and political network that was essential to advancement and even social survival…in that society.” [] [5] Ibid, 491. Here again Paul appeals to conscience. Paul says even if it is likely that the food on the table had been earlier dedicated to an idol, Christians can eat it “without raising any questions of conscience” as long as the host is not explicitly asking people to join in to a tribute to a god (10:27-28).

Through the rest of 1 Corinthians 8-10, Paul refers to this as the believer’s ‘freedom’ (9:1, 19, 21; 10:29). While the “worship principle” alone might pull us out of a culture altogether, the freedom principle critiques people who were overly scrupulous and withdrawn from culture, who felt that just being out among idol worshippers could make us somehow spiritually unclean.

That, Paul says, is to attribute far too much power to the culture and its gods. The culture does not have the ability to separate you from God just by your contact with it. Paul argues that Christians who feel this way have a “weak conscience.” They believe any contact makes them “defiled” (8:7), a word that means to be excluded from God’s presence. The over-scrupulous, then, do not have a good grasp on the gospel. A weak conscience is too easily cast into guilt and a sense of being separated from God. It does not grasp that “now there is no condemnation for those who are in Christ Jesus” (Romans 8:1). The withdrawal-party was too much like the Pharisees who complained about Jesus because “he welcomes sinners and eats with them.” (Luke 15:1) Those who grasp the implications of the gospel have an enormous freedom to participate in culture.

These two principles create a remarkably balanced, nuanced approach. As New Testament scholar Larry Hurtado concludes, Paul’s strategy combined both strictness and flexibility so Christians could be both distinctive and faithful to the uniqueness of the living God and at the same time “remain part of their families and the wider social fabric of their city.” [] [6] Hurtado, 151. Look at how balanced Paul’s advice is about private dinners. Don’t eat if the host actually is asking everyone to raise a cup to Apollos. Do eat if there is no explicit idol-tribute, even if you know the food was dedicated to a god previously.

The Love Principle

Paul knew that the principles he was laying down would not end all debate. There would be many individual situations that would not be easy to judge and to which people might apply even his wise rules differently. He knew that the different parties with regard to culture would not vanish, because they were based to some degree on personal temperament and because there was genuine room for difference of opinion about particular cases. And so he introduced a third principle to adjudicate the many difficult cases of conscience and cultural conflict—love. And this principle itself has at least three applications.

First, we must not exercise our cultural freedom if it harms other believers in any way. 8:1-3 says “knowledge puffs up”—that is, it leads to pride—“while love builds up.” “Those who think they know something do not yet know as they ought to know.” (8:1-2) Paul says that these debates about culture must be marked by a loving humility, not caustic, imperious, condescending attitudes.

And then, as soon as Paul says the over-scrupulous conservative party does not have a conscience deeply grounded in the gospel of grace (a strong critique), Paul turns back to the cultural freedom party and says: “Be careful, however, that the exercise of your rights does not become a stumbling block to the weak.” (verse 9) Some believers still feel that the idol-gods are actually present when they eat the food (verse 7). In other words, eating meat offered to idols, though biblically permissible, might lead former idol-worshippers back into subjective idolatry. Their hearts might be drawn to the old gods for “insurance.” It takes time for the gospel believed with the head and confessed by the mouth to sink deep into the heart.

You must not then, Paul says, press people to do things they may not have the spiritual maturity to do yet. The theologically and spiritually ‘strong’ and mature should not scorn the cultural withdrawal party or look down on them. They should lay aside their ‘rights’ and do everything they can out of love to maintain their relationship with the brothers and sisters who differ with them. Yes, help educate their consciences. But do so patiently and with the greatest humility and do not separate from them over it.

Secondly, we must not exercise our cultural freedom if it has a bad effect on non-believers. Paul lays this out famously and eloquently in 1 Corinthians 9.

“Though I am free and belong to no one, I have made myself a slave to everyone, to win as many as possible. To the Jews I became like a Jew, to win the Jews. To those under the law I became like one under the law (though I myself am not under the law), so as to win those under the law. To those not having the law I became like one not having the law…I have become all things to all people so that by all possible means I might save some. I do all this for the sake of the gospel, that I may share in its blessings.” (1 Corinthians 9:19-23)

Paul’s main point is that he does not exercise his freedom (for example, from the Jewish dietary laws) if that will make it harder to love and reach his Jewish brethren with the gospel. Yes, he is free, but he gladly forsakes his freedom out of love for the people around him. He constantly gives up his rights out of love, to help those around him find their way, stage by stage, into the freedom he has in Christ. “In every culture it is important for the evangelist, church planter, and witnessing Christian to flex as far as possible, so that the gospel will not be made to appear unnecessarily alien at the merely cultural level.” [] [7] D.A.Carson, The Cross and Christian Ministry: Leadership Lessons from 1 Corinthians, Baker, 2004. P.122

Paul then applies this aspect of the love principle in chapter 10. If a Christian is at a dinner party and a non-believer says “you know that was sacrificed to a god,” Paul says, “then do not eat it…for the sake of the one who told you” (10:28). This is in order to bear witness to the non-believer that there is only one living and true God. In this case, Paul asks Christians to limit their freedom out of a desire not to mislead the observer.

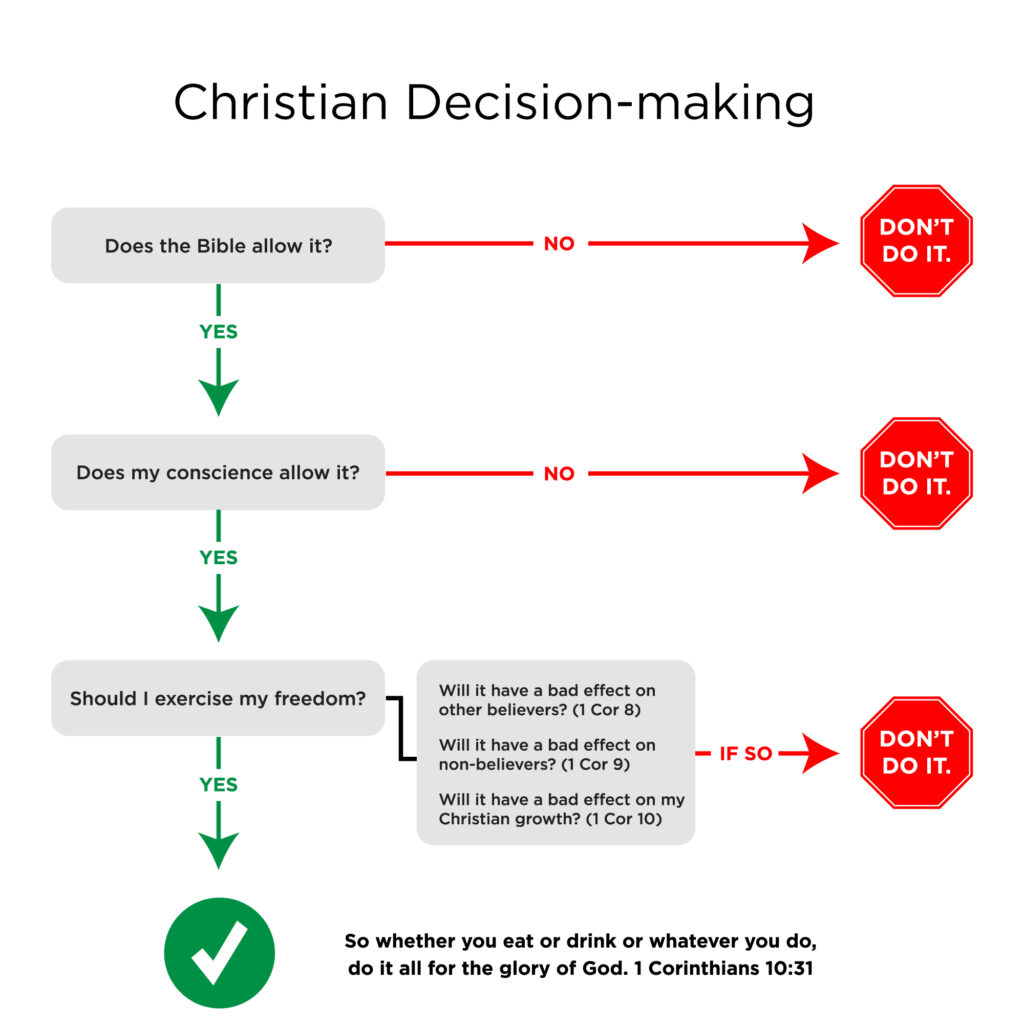

Finally, we should not exercise our freedom if it turns out that an allowed practice ends up having a bad effect on our own spiritual growth and health. (1 Corinthians 10:1-13). In his book, Authentic Church, Vaughan Roberts outlines the ‘decision tree’ of 1 Corinthians 8-10. I have adapted it [] [8] Vaughan Roberts, Authentic Church: True Spirituality in a Culture of Counterfeits, IVP, 2011, 133. :

Paul ends the three chapters like this:

“So whether you eat or drink or whatever you do, do it all for the glory of God. Do not cause anyone to stumble, whether Jews, Greeks or the church of God— even as I try to please everyone in every way. For I am not seeking my own good but the good of many, so that they may be saved” (10:31-33).

We are to stay true to God, but to do absolutely everything in our power to not unnecessarily offend, to “try to please everyone in every way” (10:33). We are not to be only ‘valiant for truth,’ regardless of whom we unnecessarily insult. Nor should we care only that no one gets upset, regardless of the loss of our witness to the truth.

Applying this Today

How do we apply this today? The Bible gives us a remarkable amount of freedom—there is no new Book of Leviticus in the New Testament, dictating exactly how we should dress and what we should eat and what we can watch and read and where we can work. Also, the gospel itself gives us great freedom of conscience. because we are saved by grace and righteous in Christ. We no longer have to fear being spiritually contaminated through contact with the world.

The Bible makes moral issues clear—we must care for the poor, love the immigrant, support healthy families, protect unborn human life, make justice impartial for all races and peoples—but it does not tell us exactly how to do so. Christians have freedom to work out for themselves how to proceed. But this has and does lead to sharp disagreements between Christians, divisions that are similar to those in the Corinthian church.

The Bible makes moral issues clear—we must care for the poor, love the immigrant, support healthy families, protect unborn human life, make justice impartial for all races and peoples—but it does not tell us exactly how to do so. Christians have freedom to work out for themselves how to proceed.

What has Paul given us in these chapters that we can use in our conflicts today?

I think the primary, radical message of these chapters is clear as we see Paul standing the modern idea of “tolerance” on its head.

For modern people, being tolerant means first, they do not make “value judgments” against anyone else; they don’t criticize anyone else’s values or beliefs. But second, they insist that no one should do that to them, either. They assert their rights to live as they see fit, and that no one can define that for them. So modern people offer no judgments, and give up no rights.

Paul is reversing this for believers. First he makes definite critiques and judgments. He says that the “weaker” brethren are weak. Their understanding of the gospel is shallow. They have not grasped yet how sharply different the Christian identity and worldview is. Christians have more freedom of conscience in Christ than the weaker brethren understand.

But then he speaks to the “strong.” They are the ones who do have much more doctrinal and theological knowledge. But in 8:1-3, he rebukes them for their arrogance and condescension. He challenges the so-called strong to give up their rights and freedoms in order to maintain unity and help believers come to common convictions and views on things. Or if they cannot agree, they should still respect the sensibilities and consciences of brothers and sisters. The modern “tolerant” person says, “I don’t criticize you, but if what I am doing upsets you that is not my problem.” The Christian says the opposite– “I do criticize you, but I will bend over backwards to keep this relationship even if it means giving up some of my rights.”

After a very similar passage, Romans 14, Paul calls the stronger Christians to “bear the weaknesses of the weak and not please ourselves” (Romans 15:1). What can that mean? It surely cannot mean we are to adopt the errors of the weak. Biblical commentator Doug Moo writes, “They are to sympathetically ‘enter into’ their attitudes, refrain from criticizing and judging them, and do what love would require toward them. Love demands that the ‘strong’ go beyond the distance implied in mere toleration.” [] [9] Douglas Moo, The Epistle to the Romans, Eerdmans, 1996, 866.

How would that work today? Here’s my suggestion. In our modern Christian culture clashes, let each side consider themselves the more mature, the stronger Christians. (We are doing that anyway!) So we should consider the letters of 1 Corinthians 8-10 and Romans 14 to be written directly to us! Now—if you are the strong Christians, you must follow Paul’s very demanding rules for the strong, along with his warnings against thinking you are so smart. Take Doug Moo’s three steps and apply them to yourselves.

First, “sympathetically ‘enter into’ their beliefs and attitudes.” Listen, with this as a test of your listening skills: Can you express and articulate the other side’s belief in such a way that they say to you, “we could not express it better ourselves?” Until the other side says that to you, you have not been patient enough. You have not been ‘bearing’ with the weaknesses of the weak.

Second, “refrain from criticizing and judging them.” It is obvious from a reading of 1 Corinthians 8-10 and Romans 14-15 that Paul does critique believers. Don’t be reluctant to do that. But you must do so with the greatest expressions of affection and respect. There can be no shaming, mocking, and denunciation in the hope they will go away. As Jonathan Edwards often says, to love someone is to put your happiness into their happiness. To love someone is to get joy out of their joy, to get pleasure out of their pleasure – and to not be happy if they are despondent. (1 Thessalonians 3:8). As Paul says, we are in this relationship “to not please ourselves.”

Third, we should “do what love would require toward them.” There are always two basic things that love requires. First, we must tell loved ones the truth and get them to study more thoughtfully biblical truth. That means helping people understand more fully the uniqueness and depth of the gospel identity and the Christian worldview.

Much of our cultural and political conflict happens because Christians are so deeply influenced by social media and news feeds, which create echo chambers. As Paul would say, the effect is to “weaken our consciences”—making us slaves to particular secular ideologies of left and right, all of which are based on secular, one-dimensional, non-biblical accounts of human nature and moral values.

Christianity appreciates all cultures (the concept of “common grace”), but critiques every culture as well—including every secular political and social theory. If Christians were far more educated in this kind of biblical theology, they would have more freedom of conscience (rather than being pawns of political ideologues) and more appreciation for Christian brothers and sisters with different political affiliations.

Finally, regardless of whether other Christians grow in their understanding of biblical truth the way we understand it, in love we are to do everything possible to stay in relationship, to stay in community with other believers, even those with different cultural opinions. It may mean that in your local congregation you don’t get your way in a number of areas. The worship music is not as you’d like it. The preaching is not as emphatic about certain topics as you’d like it to be. As Paul says throughout, that may mean refraining from language and practices that you believe are valid, that you have a right to, but that grieve some of your brothers and sisters. If they are making their own sacrifices toward you in love, then there is a genuine possibility of a growing unity of mind. (Philippians 2:1-4)

How is all this possible? Christ makes this possible. When Jesus went to the cross he was making one of the most negative evaluations of us possible! When he died on the cross, he was saying, “You’re so lost that nothing less than the death of the Son of God will save you.”

But at the same time he was entering into our condition, making himself vulnerable to us, making room in his life for us, sacrificing for us.

There are enormous resources in the gospel for being receptive and loving to people with whom we deeply differ. If you build your identity on what Jesus did for you, you will become something far better than ‘tolerant.’ You will be able to disagree honestly and sharply with people and yet do so without the slightest bit of ill will, without the slightest need to exercise power in those relationships and friendships, without the slightest bit of superiority. We will be able to sharply disagree with all love, respect, deference and humility.

Secularism does not give us the resources to have these kinds of conversations and relationships, as desperately as we need them. Secularism says, “Let’s all be tolerant, our way! You’ve got to adopt our relativism, our skeptical epistemology – or else we will consider you not SAFE.” That makes a mockery of the very idea of tolerance. Christianity says, “Jesus sacrificed his freedom so we could be accepted as we are– and yet that sacrificial love enabled us to grow and change. We will try to love you in the same way.”

Right now, the church looks more like the world. But that is not what the world needs from us. There are few things more needed today than millions of Christians who know how to talk and love across barriers of difference.