I recently performed Wynton Marsalis’ A Fiddler’s Tale, a contemporary musical reimagining of the classic Faust story, and was struck by its relevance to my own life and work, given Marsalis’ twist: The Faustian subject is an artist, a fiddler. In discussing the work with Mr. Marsalis and our colleagues, I found that (contrary to a popular opinion), deals with (and temptations by) the devil still resonate, [] [1] Anaïs Mitchell’s Hadestown, Thomas Mann’s Dr. Faustus, and (older but still iconic) Stravinsky’s L’Histoire du Soldat (from which Marsalis and Crouch found inspiration) are all great examples. perhaps even more so in our “disenchanted” age.

Throughout the tale, the devil (the B.Z.B.

[]

[2] Beelzebub

) breaks the fourth wall to reveal the compelling artistry of his seduction:

NARRATOR: [The fiddler’s] name is Beatrice Connors. She has the power to lift the bandstand, but the burden of her own glow, in conflict with her inky desires, wears her down.

FIDDLER: I’m angry at this business. I hate the nature of success, but I’m envious of it. No, no, I just want more people to enjoy things like this tune by the legendary fiddler, Uncle Bud.

NARRATOR: She’s floating on a dream cloud of celestial notes. Bubba Z. Beals approaches. He is almost moved by her softness and her power. But being moved is not his line of engagement. The B.Z.B. begins talking with her.

DEVIL (to audience): I’ll slip into her soul through the window of need. She wants to be known; I’ll tell her I recognize her. She will be surprised.

Note that the B.Z.B. sees Beatrice and preys on her need to be known (not a sinful desire, except in misdirection or disorder). In counseling parlance, the devil works through her “deep idol” of approval, by presenting the bait and hiding the hook.

FIDDLER: That makes me feel good, but even if you didn’t know who I was, we would still be out here playing. We are not giving in.

DEVIL (to audience): Now I drop the payload. I tell her she is, oh, man, just so great. Then I tell her, I wish she made recordings. That I am in the music business myself and even I can’t find her sound anywhere. I would just love the opportunity to sit alone with a recording and sink down into the invisible glory of her sound …

FIDDLER: I’ll say what I was really thinking. Well look, I used to be ashamed of wanting to be appreciated, but now I know that’s stupid.

Artists can wrongly repress our desire for appreciation, honor, and approval (all good desires). But we can also wrongly untether our desire for those gifts from the God who gives them, losing trust in his mysterious timing and methods that maximize his own glory (and the good of his children). The devil is very shrewd at inching us down this path of distrust; just ask Adam and Eve (Genesis 3:1-6).

Later on, as Beatrice grows more successful, the B.Z.B. adds another requirement to their agreement:

DEVIL: Change is an expression of humility. The seasons do it. You need to drop that elitist sneer and lilt the public with simple music from the heart. There is power in simple things. Wouldn’t you like some power over your audience?

FIDDLER: In my circle we don’t care about the love of the public. Actually we do. I hate to admit it, but I would definitely like to have that power. Who wouldn’t?

DEVIL: Admission, my dear, is very good for the soul. I know where there is power to be plucked like a violin string. Give me that old violin. I will give you the power to be born again. Millions will love you. Come on now. The violin … good.

With Beatrice already hooked on approval, the B.Z.B. offers her a second idol of power, if she will only hand over her gift (the violin) to him. [] [3] “Next the devil took [Jesus] to the peak of a very high mountain and showed him all the kingdoms of the world and their glory. ‘I will give it all to you,’ he said, ‘if you will kneel down and worship me’” (Matt 4:8-9, NLT). In the original script, the devil tells her to “reach up, stick your thumb in, and twist [the sun] out like a light bulb. Make the world black. And then we will make the moon rise.” Blot out the source of light, and set yourself in its place. [] [4] This pattern of overthrow and succession is congruent with an early interpretation of Isaiah 14, which ostensibly described the pride and envy of the devil, his desire to overthrow God, and his subsequent fall (cf. Origen’s De Principiis). This is a sound illustration (even if not exegetically watertight).

Five years later, Beatrice is trapped in worldly “success,” degraded by the B.Z.B.’s “improvements” on her artistry (largely sexual in nature), and bitter:

FIDDLER: You bubble-headed liar, you used me!

DEVIL: Here we go. Use or get used, that’s the story of the blues. You’re doing all right. For somebody who pimped herself.

FIDDLER: Oh no, I got duped. I was kidnapped from my audience, from my students, from all the talented, young kids who look up to me. I’m just a prisoner of your lies. Everybody knows I’m just doing your program.

DEVIL: Right, less than less is always worth more. Learning to whore might be a chore, but if you do it, you will never be poor. You were exquisite.

FIDDLER: I have enough bitterness in me to turn my blood to poison.

DEVIL: Calm down. Take pride in yourself. I did.

FIDDLER: I’ll never be proud of that.

DEVIL: You should. You were as good as they get. Remember your relaxed willingness to corrupt the young when they were in the first bloom of romance. You gave them a little bit of music and a whole heap of mmmm hmmm hmmm. They were young suckling pigs at the breast of spiritual pollution. So that’s the mechanical pace. Don’t whimper about the race.

Beatrice finds herself in the same place as the younger brother in Jesus’ parable of the Prodigal Son (Luke 15:11-32). Having wasted her gift impatiently, and fallen for the devil’s schemes, she seeks to make it right. Through the help of the narrator and her inspiring mentor-figure Uncle Bud, Beatrice tricks the devil, reclaims her violin, and uses her music to bring life back to a mysterious savior, who is bedridden with illness:

SAVIOR: I was lost because the world was so, so sick. Through the perpetual act of faith the savior is saved. My child, you have learned the source of your soulfulness, which is the willingness to give. You have been illuminated by humility … There is no god greater than the “I am” of pure intent.

To Christians, this “savior” seems odd, until we remember the source material. Like the old pagan myth of Orpheus (and the Hadestown retelling), Stravinsky’s story (an old Russian tale) featured an aspirational (but tragically flawed) savior figure, a soldier who recaptures his gift from the devil in order to save a princess. But in The Fiddler’s Tale, this heroic frame goes one step further and fully inverts orthodox soteriology: “through the perpetual flame of faith, the savior is saved.” This deification of “faith” (the god of “pure intent”) is itself a subtly disguised third deep idol: control, the enticing snare of works-righteousness. To use Tim Keller’s language in The Prodigal God, Beatrice the “younger brother,” tries to become an “elder.” But she won’t last long.

NARRATOR: But Beatrice Connors is Beatrice Connors. With the savior going from sickness to sickness, lifting spirit ofter spirit, the work of pure intent wears her down. At a mass saving, with soul after soul lighting like endless candles in the night, the fiddler realizes that she is back to where she started, small and loved, but outside of the big action. Trapped again, she screams. She runs away to the South looking for Uncle Bud. She breaks her fiddle and is about to lose her mind. She sobs and sobs at the bank of a river.

Artists prone to the idol of control and elder-brother behavior (also not uncommon for those in “professional” ministry) know this feeling, the breaking point where you come to the end of yourself, after a period of attempting reliance on the flesh to do the work of the Spirit.

[]

[5] See Kathy Keller’s description of this dangerous reliance on the flesh in the context of “faking it” in ministry: “And after a while you hardly even admit to yourself you’re faking interest in the other person, faking enthusiasm for Christ and his gospel, faking your entire Christian life, because you don’t even recall what it was like to have a vibrant relationship to God. You have become hollow. You may still look and sound good on the outside, but inside the reality of God’s presence is gone.”

But in Beatrice’s case, she never had the spiritual presence at all. Brought to the end of her own capacity, she leaves the “savior” she helped rescue, she seeks comfort in anything (the fourth idol).

NARRATOR: Then Uncle Bud appears. Uncle Bud sheds tears, too. He is disappointed. He weeps more loudly than she does. He cannot say anything. But he will try something. One last attempt on the straight and narrow. He removes a bottle from an ancient case.

UNCLE BUD: Drink this. It is a potion that may return you to the true faith.

The true Beatrice Connors (and the true object of her faith) is revealed in the final scene of this tragedy, and she is exactly as the narrator originally described her: “She has the power to lift the bandstand, but the burden of her own glow, in conflict with her inky desires, wears her down. [She’s] angry at this business. She hates the nature of success, but [she’s] envious of it.” [She thinks she] just wants people to enjoy [beauty, like the music of] Uncle Bud. But Uncle Bud (and even the tale’s “savior”) would never be able to fulfill Beatrice’s desires or bear her weight of glory. The devil knew it all along.

FIDDLER: Oh. Oh. This is the worst thing I have ever swallowed. Oh, I feel so sick …

UNCLE BUD/DEVIL: Uncle Bud, Uncle Fud. This is me. This is the B.Z.B . … I just used you to keep the game from going dull. It’s your time now. So I can put my foot on your skull. Little girl, you are drawing your last, free breath. This is the taste of B.Z.B. manufactured death.

FIDDLER: No, please, Uncle Bud … Uncle Bud … Unc … (deep, deep desperate breaths, then a final gasp).

UNCLE BUD/DEVIL (laughing): Yes! I’m coming up smoke stack tall up out of my hole. And you, audience member, had better keep a good, good, good lock on your soul.

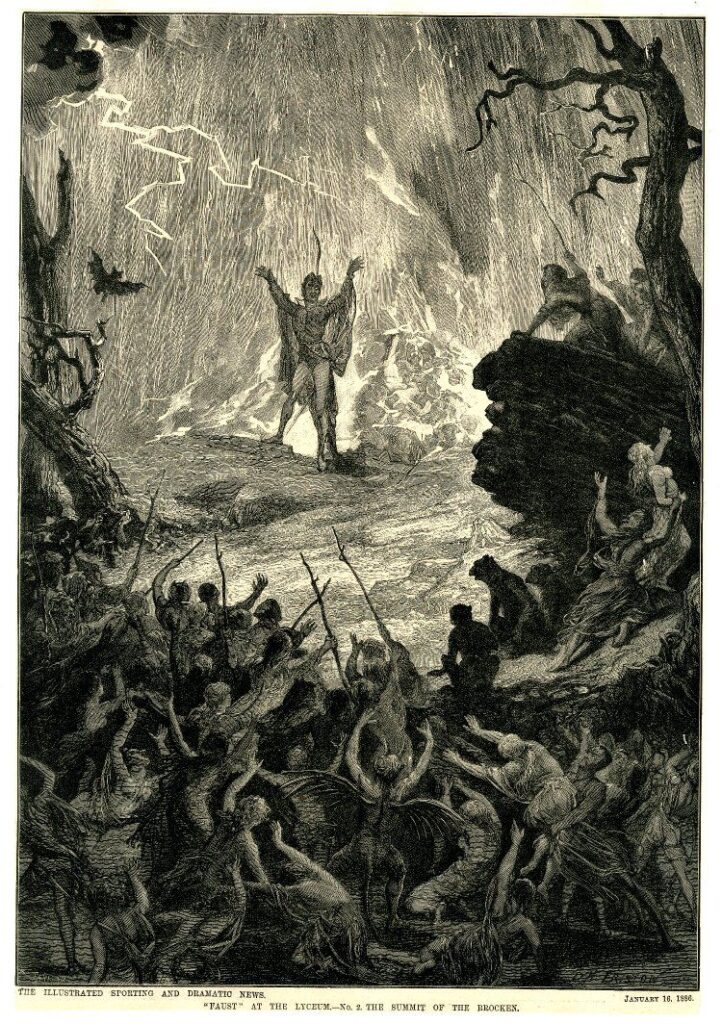

The end is sobering, but what is the actual meaning of these tales, and how ought we to respond? Repurposing the Faustian stories as tales of “liberation” (usually accompanied by flippant ridicule of “fire and brimstone”) is one approach, but they are not simply farce. Cathartic retelling of tragedy as an exercise in expressing (wishful) hope is another approach, but they are not simply fantasy. I’d like to add a third perspective, to see them as sophisticated literature with an unreliable narrator.

In The Fiddler’s Tale the devil wins and gets the last word; in a sense, it’s really The Devil’s Tale, not Beatrice’s at all. Uncle Bud, the “savior,” and Beatrice herself are just tools in his mighty plan to dominate, consume, and destroy. But if the devil is the father of lies, and he’s the one telling the story, [] [6] While this unreliable narrator frame is generally implicit, a more lucid, comedic approach may make it explicit (ie. Me Supremacist by Martin Landry): Hello. I am the devil, and I am a liar. Let’s sit with that for a moment. Now, am I telling a lie, that I’m a liar? Or am I telling the truth, that I’m a liar? Either way, if I’m telling the truth that I’m a liar, or if I’m telling a lie that I’m a liar, that means I can tell the truth. Right? That’s why I’m here tonight, to tell the truth. Before I go any further, I’d like to open with prayer . . . what might he want to leave out? The true gospel of the true savior, of course.

So for the Christian artist, the Faustian tales can exhort, but only if the gospel is first planted deep in the heart. Of course we should know ourselves and our sensitivities, order our joys and loves rightly, see that our gift(s) are good but that our Father the Giver is better. [] [7]As John Piper recounted regarding his last exchange with Tim Keller (reflecting on Luke 10:20): “Be more thrilled that you are saved than that you are successful; take more delight in the [actual] savior than in his service.” (bold and italics mine) We should spurn the devil’s offers of comfort, control, approval, or power. But if we fail in any of these, we must reject his most pernicious and enduring lie: “Now, earn your way into God’s favor.”

Repentance is turning to our Father. It is not a reward for the gifted artist to achieve. It is a gift for the humble artist to receive. Jesus will win over the devil’s lies, and he desires for each of us to participate in the victory with our gifts —not because he needs us, but because he loves us. As Luther’s hymn puts it:

A mighty fortress is our God, a bulwark never failing;

our helper he, amid the flood of mortal ills prevailing.

For still our ancient foe does seek to work us woe;

his craft and power are great, and armed with cruel hate, on earth is not his equal.Did we in our own strength confide, our striving would be losing;

were not the right man on our side, the man of God’s own choosing.

You ask who that may be? Christ Jesus, it is he,

Lord Sabaoth his name, from age to age the same, and he must win the battle.And though this world, with devils filled, should threaten to undo us,

we will not fear, for God hath willed his truth to triumph through us.

The prince of darkness grim, we tremble not for him;

his rage we can endure, for lo, his doom is sure; one little word shall fell him.That Word above all earthly pow’rs, no thanks to them, abideth;

the Spirit and the gifts are ours through him who with us sideth.

Let goods and kindred go, this mortal life also;

the body they may kill: God’s truth abideth still; his kingdom is forever.

Harrison Hollingsworth is a bassoonist and conductor with NYC Ballet, and he helps direct music at Redeemer Downtown. He, his wife, Leah, and their three children make their home near Lincoln Center.